Last of Babylon

‘Qen-Ra watched the night fade and the sky brighten over the sand dunes and tan bluffs just beyond her father's half-acre plot. The air smelled of rain even though the sky was cloudless, as it had been for months. It was her first task every third morning to lift the rusty iron sluice and submerge the field with water from the ancient canal. She was tired from lack of sleep and trying to lift the heavy gate, but the rain scent made her happy as she stopped to gaze at the disappearing stars. She whispered thanks to Anu, keeper of the heavens, and to Shamash the sun god to be merciful to their meager bounty, then noted the positions of the stars before they winked out, along with Sin, the half-Moon, and her beloved adamantine Ishtar, a beacon unwavering against the onslaught of light from the east.

‘Her late mother had sometimes told her that the stars chose our fates, conspiring with the wandering lights that moved among them to undo everything we might strive to achieve otherwise. As Qen-Ra grew older, she wondered if this was only a joke aimed at her father's laziness. She and her mother had always done the lion's share of work to keep food on the table, often under the harsh afternoon Sun, when Shamash transformed into Nergal, destroyer of life, lord of the dead. While they toiled her father stayed inside the mud and thatch hut, experimenting with his recipes for date palm wine. He occasionally brewed a good batch that brought some money at the bazaar, but he eventually acquired the habit of drinking his profits. Too many times they had come in from the field even before noon and found him passed out, only his bare feet visible among the cluttered clay jars.

‘Often during idle mid-mornings or late afternoons Qen-Ra and her mother would escape the heat down by the river, since the canal was too shallow to swim in. Half a league distant, the Euphrates was a broad, shimmering plain of water bordered by woolly green and pink tamarix, always reminding reminding Qen-Ra of rumors she had heard of the distant sea, far beyond even the land of the strange Chaldeans, where the rivers met their end. Gilgamesh had met his greatest adventures there, and though she often dreamed of what lay beyond the borders of her village she did not believe she would ever have the heart to travel all the way to the tumultuous ocean.

‘In the summer of her twelfth year the heat was so unbearable that their hut became uninhabitable during the day, and even her father, complaining that the weather was souring his palm wine before it was ready for market, sought refuge from it. Qen-Ra remembered that even the dragonflies kept to the shade along the water's edge. The river was high, swollen by the previous winter's rains and the snowmelt from the northern mountains that, like the sea, were only a rumor to fire a child's imagination. After intoning a prayer to Enlil for protection, she and her mother slipped off their sweat-soaked tunics and entered the water under the cover of a drooping tamarix. “Qen-Ra saw the boat first, a reed canoe that looked to be able to seat at least eight, lazily spinning with the current. It was trimmed bright orange along its raised prow and stern, and two pairs of oars dangled from their locks. Her mother called to her father, who was reclining on the bank with his feet in the water, but he could not be bothered. “It's royal property,” he yelled, lying back down. “They'll execute us all if they find it in our possession.”

‘Qen-Ra watched her mother stare frantically at the boat, then in disbelief at her father. “You idiot!” she finally shouted. “A royal boat wouldn't be drifting upstream from the city!” And off she swam.

‘Qen-Ra started after her, though she was an awkward swimmer and had never dared the deep water before. Her efforts had not brought her far, though, when she recalled the tales of the three great floods he had witnessed, one of which had reduced his home to a lump of mud and straw and carried off his ox and goats. She had learned young to respect the river's great power, and she was learning even faster now, seeing the panic on her mother's face just before it slipped below the surface once, twice, a third and fourth time. The fifth was the last. Torn between her fear and the urgent thought that her mother was about to die, Qen-Ra began kicking and stroking in the direction she last saw her, and was immediately spun like a helpless wrestler onto her back, the Sun blinding her. The swift eddies that had claimed her mother pulled her under and turned her over again and again, and with all her strength she regained the surface, gasping for air, and started back toward the shore. She ended up crawling onto a sandbar near the site of the village bazaar, her naked body eliciting hoots from the men who sold tin rings and bracelets and filigree, and the sympathy of the older women, who came out from behind the carpets they hung from their booths to wrap her in a spare robe. Once she had regained her composure she thanked them and began the walk back to find her father, keeping to the shade of the palms to spare her bare feet from the burning sands.

‘Through her tears she saw that her father had not lost any sleep over the matter. He was still lying on the bank, his feet dangling in the water and his clay jar beside him.

‘Qen-Ra stood before the Ishtar gate at dawn and silently gave thanks to her protector on high. It was yet visible, low in the sky, almost lost in the glare, soon to disappear, she knew, into the heart of Shamash. She had travelled the seventeen leagues by night to evade the desert heat, even though autumn was well underway, but also to avoid human predators. In the bag over her shoulder she carried an extra tunic and headdress, and enough flatbread to last three days. Hidden in the folds of her clothing was her father's money purse, containing what little he had ever managed to accumulate at any one time. Though there were towns and villages along the way she slept in groves along the river, still mourning for her mother after three years.

‘She had not prospered under her father's care. If the abuse of being blamed for her mother's death by him wasn't bad enough, it was compounded by having to shoulder all her mother's responsibilities as well as whatever he did not feel like doing anymore. There were the regular cuffs and beatings when he got drunk, or judged her work less than satisfactory. On perhaps a dozen occasions he exposed himself to his daughter, but always stopped short of raping her, and she guessed it was for the same reason that she never had any brothers or sisters—her father knew a pregnant woman did not perform her tasks with as much efficiency. Now, with any luck at all, she could devote her labors to far more nobler pursuits. The gates were not yet open for the day, so as she waited among the handful of other travellers, farmers and merchants seeking entrance, she recalled the day that had set her firmly on this path.

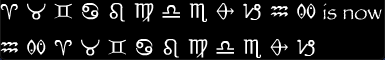

‘It had only been a few months after her mother drowned. She went with her father to the bazaar, wearing a headdress so the men would not recognize her. She wandered off while her father haggled over the price of his palm wine, and came across a dark woman she had never seen before seated in a cloistered booth, seated on a large carpet embroidered with icons of the Sun, the Moon in all its phases, and the constellations. “Come closer,” she beckoned in a husky voice. “Let those who rule the sky tell you of your fate.”

‘As preposterous as it sounded, Qen-Ra found herself drawn by the woman's invitation. In another minute she had relinquished the coins she had planned to spend on a new pair of sandals.

‘The woman introduced herself as Ronama of Chaldea. There was a salty odor on her breath and her hands told of a life of toil among the endless swamps where two mighty rivers lost their way. She immediately informed Qen-Ra that she was singly under the influence of Ishtar, went on to say that her sign was water, and ended by predicting that she would one day follow her protector star to fame, though perhaps not fortune, in the big city.

‘Babylon's best days had come and gone, never to return. The rule of Hammurabi was a forgotten legend of another millennium, and even Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar were names beyond the memory of even the eldest. The Israelites had broken their bondage and escaped over two centuries past, and the Persians had been chased back to their mountainous realm by the Macedonian armies of Alexander. Even they were quickly tiring of the novelty of this conquest, succumbing to homesickness and the siren call of their islands and olive trees, leaving the natives to their devices. As Qen-Ra shook the sand from her sandals she was overcome by a sense of futility and especially of arriving too late, not only because of the locked gate but also by the sight, as she looked east along the receding perspective of the city's northern wall, of the enormous dunes piling up nearly to the parapets.

‘Inside, however, the city yet thrived, at least by a country girl's standards. As she and the other travelers entered the newly-opened gates street vendors closed in on them, hawking all manner of goods—fabrics, fresh vegetables flatbread, fish from the river that flowed through the city's heart. Qen-Ra heard the fisherman above the hubbub, bragging that his catch came from waters well upstream, free from contamination, and she knew instinctively he was lying. Farther up the Processional Way she encountered the faded glory of the ziggurats reaching for the sky, some still bearing faint traces of the colors they had once been meticulously painted at each level. She noticed that now they all carried fresher coats of paint—brazen merchants had scrawled their sales pitches in vivid tones across the weather-worn bricks—and though she could scarcely read she just as instinctively knew what they were by the way the messages pressed upon each other and fought for space at every level, like the vendors who lined the streets in every direction.

‘Qen-Ra knew she, too, had a marketable commodity. Unlike the hawkers waving their wares, though, she had no way to openly display it, for it resided in her head. And unlike the innovative souls who chose to deface the ziggurats in the name of commerce, she could not openly advertise it for a potential buyer, even were she literate. The mysteriously Chaldean woman had warned her, with a sigh that reeked of nostalgia for a certain salt marsh, that there were some things a girl was not supposed to know.

‘The view of the sunset from the ziggurat was certainly worth the climb. Panning her gaze from the dull crimson hovering above the dusty horizon to the pink clouds against the cobalt blue vault of the darkening sky and the lighting of oil lanterns in the streets below complemented by the quickening stars above, Qen-Ra felt a unique exhilaration. Her sense of well-being was heightened by her full stomach, having just eaten of her first satisfying meals since leaving home, so she felt both alive and a bit sleepy at the same moment. The only thing spoiling the occasion was the cool breeze stirring above the walls of the city— it being about the closest it got to the dead of winter— that found a way of penetrating her tunic. Her nipples were hard and she had to take care not to reveal her condition, even if night was falling fast, so she crossed her arms across her chest and feigned a chill.

‘She was not alone. Her performance was meant for the deep brown eyes of Khaliz, a fellow student at the royal school of astronomy. Khaliz had offered to treat her to dinner after the day's lessons, and they dined on a slab of roasted goat, a barley loaf and a bowl of dried apricots. They walked off the meal along the Processional Way afterward, and as the day ended they clambered up the crumbling brick steps of the ziggurat for the best seats in the house. Halfway up, Khaliz asked her to venture a guess as to why the proud and industrious citizens of Babylon had built so many of the steep-sloped, multi-levelled pyramids like the one they were now ascending. Qen-Ra, her head still spinning a little from her whirlwind acceptance into the school, answered that it was so they could be closer to the stars.

‘Khaliz had a good laugh at that one. “No, silly. It was so they could have somewhere safe to go when the floods came.” Khaliz claimed to be a Chaldean, so Qen-Ra had to wonder how he could know so much about the ways of Babylon. He had already escorted her to half a dozen of the city's landmarks, including the Hanging Gardens, where she reveled in the botanical delights of faraway Persia, Assyria and now Hellas, the aroma of humus and dead leaves, and especially the humidity. The Euphrates had never smelled like rain, not until it interacted with the soil, and here the irrigation water flowed freely from one level to the next below, over the brickwork and their feet. Qen-Ra felt the dry skin of her forehead and temples relax as the pores opened to drink it all in. Scanning the exotic flora as the guide described their far-flung origins, she had the distinct sensation of being uprooted and replanted far from her natural habitat, so much so that she did not have the least idea what her natural habitat was anymore. She remembered the woman with the salty air who told her fortune at the bazaar, how she compensated for her strangeness by making customers seek her out, and she realized with a brief swirl of vertigo, up there above the city, her precarious her situation really was. Khaliz, and everyone else at the school, believed she was a boy. “Qen-Ra also drew on her memory of the woman when she underwent her admission to the school. Not knowing what else she could do and with her money almost gone, she pressed a palm-reader in a marketplace by the river for a reading in exchange for reciting for him the positions of the planets at his birth. It was a long shot, but the reader, who seemed to be suffering a premature decline of vision by his peculiar one-eyes squint, was amused by such a bold claim.

‘“Boy, only the royal stargazers can tell those things for sure,” he laughed. “Nobody can remember what happened twenty-six autumns ago when I was born, and it's a safe bet you weren't around then. Go right ahead.”

‘Qen-Ra rapidly made the mental calculations, just as she had done more leisurely on mornings before dawn Twenty-six years made reckoning the positions of the slow wanderers easy. Pinning down the blood-red star was a bit trickier, but it too moved in cycles roughly parallel to the Sun's. Ishtar, in her elliptical courses, never straying far from the Sun, was the hardest by far, though, and she deliberately saved it for last.

‘“Amber planet— sign of the bull. Silver planet— sign of the scorpion. Red planet— sign of the fishes. And Ishtar— ”

‘The palm-reader leaned in closer, squinting harder than ever.

‘“Sign of the lion.”

‘The palm-reader laughed, and she heard his laughter echoing behind a curtain at the rear of the booth. It parted to reveal an older man lying on a cot, his parted lips revealing a toothless grin. Qen-Ra's heart was in her throat a moment, thinking him a leper, but she saw none of the tell-tale rot around his fingers and nose, and realized he was simply a bed-ridden cripple. “Just as the royal astronomer recorded it, son,” he said, ending the palm-reader's amusement cold. “Looks like we've got ourselves a new attraction.”

‘Almost overnight, the palm-reader's shingle came down and Qen-Ra began earning her keep casting charts for anyone with a firm birthdate and two pieces of silver. At first she was grateful merely for a place to sleep out of the streets, even with father and son's snoring from behind the curtain, and steady meals But as her reputation spread and business became brisk, she soon discovered she was a virtual prisoner. Not only were the father and son keeping every sliver of profit for themselves, but the father was always there to watch over her, and criticizing her treatment of customers during every lull.

‘“You're making too many people sad. Send them off with better fortunes. Then they'll come back for more.”

‘Not that it was going to affect her fortune one way or the other, nonetheless she followed the father's advice. But then she began adding her own twist— telling customers their futures awaited them beyond the walls of Babylon. She scattered them to the four winds— a camel trader to the southern desert, a musician to Persia, a fisherman to Chaldea and the sea beyond— until the father was screaming at her and threatening cuffs they both knew would never be delivered. The son, who was frequently absent now, enjoying the time off and the easy money, would certainly not beat his cash cow— yet.

‘Her sexual deception notwithstanding, Qen-Ra just wanted to be honest with her customers. From the day of her arrival, seeing the sands encroach upon the walls, she saw Babylon for what it was— a doomed city. Its inexorable slide into oblivion was nearly complete. The ruling elite, such as it was, clung to vainglories of the past like the Hanging Gardens while the rest of the city crumbled and crass merchants were allowed to deface the once-sacred ziggurats. Qen-Ra saw it all. To be sure, the ruling elite saw it, too, but considered it only a case of returning to good graces with the gods. To that end, they summoned the royal astronomer Kiddinu, who had already decreed that days begin at midnight and determined that the Age of the Ram was nearing the end of its two-millennia run. Spare no expense, he was told. Train the best astronomers in the world. Tell us what the stars foretell, and how we may avoid the worst.

‘And so, one cloudy morning, a retainer of Kiddinu sat before Qen-Ra, who cast the chart of his birth thirty-four years previous to perfection. Over the shrill protests of the invalid father, the retainer led her away and escorted her directly to Kiddinu's compound. There she waited outside the great man's door, sure she was in some trouble, until well into the afternoon, getting hungrier as the minutes dragged. At last, Kiddinu himself stood before her, commanded her to rise. He placed a blindfold over her eyes, spun her around seven times, then ordered her to pinpoint the positions of each planet and the Moon at that very moment. Qen-Ra thanked Ishtar that at least they were still outdoors then, with only the thin warmth of the clouded Sun on her face as a reference point, she did as she was told, indicating the ground below her feet at varying angles for three planets that were below the horizon.

‘“Well done, my boy. At least you understand the Earth is round.”

‘“Hellas.”

‘“What?“

‘“That's what they call their land. Hellas. The Hellenes.”

‘“Oh,” said Qen-Ra. She stretched her naked torso languidly, pulled the blanket up under her chin, reached for Khaliz beneath it. She was glad now she had revealed her true self to him, for he had responded so positively that she felt she had gained everything by taking the risk. Not only had she found a marvelous lover, eager to satisfy the yearnings he had awakened in her from the first day she saw him, but her future was now opening up like the blossoms at the Hanging Gardens. From the moment they had first made love two weeks before, they had talked about little else except their plans to stay together and make the most of their talents.

‘“Hellas is almost completely surrounded by water. And they have islands, like the sandbars in the river, but they're huge, some of them, like ziggurats rising up out of the sea.”

‘“How do you know all this? Have you been there?“

‘“No, but they've been coming here for years. Some even say we belong to them now.”

‘“Funny.”

‘“They're fascinated with us. They want to know more about our astronomy, and especially how to read the future. Once we complete our studies they would take us there. We could leave this hot dusty hole behind forever.”

‘“Will you tell me the next time one comes here?“ She wanted to ask if a land surrounded by water always smelled like rain. It didn't really matter, of course. They had already set their hearts on going. And what a team they would make! Khaliz did not have quite the knack for charting the heavens as she— in fact, the first few times Qen-Ra supplied correct answers in class she was sure she detected hostility simmering just behind his eyes. But when he later approached her offering friendship she decided her first intuition was wrong. Khaliz was certainly cute, with sleepy brown eyes that crinkled at the edges whenever he laughed. Despite her masquerade, she figured he would make a good catch, and as long as he was with her she could be sure he was courting no other females. What he did have to make up for his lack of talent was practicality. He knew how to flatter people to get what he wanted, where to find the best of every commodity, and seemed to know simply everybody no matter where they went. She thought that strange, since he claimed to be native to faraway Chaldea.

‘“Oh, that's because I never forget names and faces,” he explained.

‘Misgivings whispered in the back of her mind eventually gave way to the realization that if she was ever going to see Hellas, much less survive there, it was going to be with Khaliz's help. She knew that if she were ever going to amount to anything as an astronomer, someone would have to be there to take care of down-to-earth things while her mind sailed the skies. She also reasoned, with no small encouragement from Khaliz, that he was going to have to pass all his courses if he was going to make it to Hellas. So she began tutoring him in the areas where he was having particular difficulty. She started by recasting his natal chart for him, showing him the significance of trines, squares and sextiles, and especially a planet in retrograde. “Ishtar, what you say the Hellenes call Af-ro-die-tee, goes backward about every nineteen moons. Not a good time to fall in love,” she told him. She made sure he understood the declinations of stars, for if they were off to a land surrounded by water it would not do to be out on a boat without the ability to reckon latitude. She detailed the thirty-year cycle of the Moon, the fifteen-year cycle of the Red Wanderer, the fifty-two cycle of Ishtar. She prepared him for their final examination, which was to accurately predict the date of the next lunar eclipse.

‘“Start by calculating dates of full Moons for the next three years,” she instructed him.

‘In retrospect, she realized perhaps she shouldn't have been so condesceding. She also kicked herself for trivializing something she had noticed but never mentioned in casting his chart— that he was born under a retrograde Saturn in the sign of the scorpion, an omen of someone in whom trust was a devious investment. Her first hint of something amiss was the moment Kiddinu indicated her wanted her to remain after his lecture on the astrolabe. It had been a day of winter rain, the time of year that would come to be known as February, and Qen-Ra had been so distracted, preferring to be out in open spaces, maybe even the Hanging Gardens, to revel in the rare humid air. She heard Kiddinu call her name and was sure he was going to chastise her for her inattention. Khaliz stayed, even though he had not been asked to, and she felt the first tickle of panic. They had never shown the slightest indication of any acquaintance anywhere on the grounds of the school, the better to keep her deep, dark secret. She shot him a look meant to ask What are you doing? but he only stared impassively ahead. Ever the optimist, she considered the rumor that the royal astronomer was in hot water with his patrons for a prediction he had originally made in class— that the coming age would usher in a new religion based on that of the Hebrews, just as the Hebrews had borrowed from the creation myths of Babylon at the distant dawn of the present age— and that he was going to enlist his two brightest students in his defense. The wise man opened the door for both of them to his chambers.

‘Hearing the rain falling through her teacher's window was the last pleasure she wold ever know. Kiddinu had only to nod and Khaliz was there to shred her tunic from the shoulders to the knees before she could even catch her breath. She stood shivering as Kiddinu surveyed her like the heavens themselves— her petite nipples that Khaliz said always indicated the zenith whenever she lay supine, her long skeletal arms, her sex, or lack of it. Kiddinu said only that the temple of the ritual prostitutes would love to have her but that the crown could never forgive the theft of esoteric knowledge. The last she saw of Khaliz he was accepting congratulations from their teacher. “Your father the prince will be proud. You shall certainly lead our next delegation to Hellas.” The two soldiers led her away to the stables where they took turns raping her from mid-afternoon until the clouds departed and the full Moon rose above the walls. The stars wheeled and the horses neighed skittishly at her cries, and to keep her mind clear she reckoned the dates of eclipses for the next two thousand years, all the way to the age of the Water-Bearer, the sign the Chaldean woman had said influenced everything she did.

‘They then bound her and dragged her in the direction of the river, and as the Euphrates closed over her head and the taunts of her tormentors were replaced by the effervescence of air bubbles escaping what she could not, she knew she and the old woman were simply trading places, and that she had every bit the nerve to make the journey to the sea.’