Speaking in Tongues

Just after starting out Gregg spotted smoke reflecting the light of dusk, and it alerted us to the presence of a large olive-drab tent set up behind a windbreak of leafless poplars. The tent’s military appearance was cause for alarm, but upon seeing only a few cars parked outside Gregg decided we would not be too far outnumbered and turned off the road to investigate. But the tent hid several more vehicles, including a large RV. In its shadow a boy of about fifteen was tending the fire, over which a large black kettle hung suspended by a tripod. Upon seeing our truck approach he quickly dashed inside the RV. He returned with two older boys, both armed as we were with holstered pistols, and an elegantly robed, balding man of about forty.

“Peace, fellow pilgrims,” said the robed man, raising a hand with two fingers extended. “From where do you come?”

“Dallas,” Gregg answered hesitantly, eyeing the silent boys with the guns.

“Dallas!” The robed man looked startled. “Why would you then travel in the direction of endless night? The love of God is hardly to be found in these realms, let alone farther north.”

“We search for lost friends and relatives,” Gregg responded, probably unaware of slipping into the older man’s pattern of speech. After LaMaze, I saw he exerted a great deal of influence on anybody around him. He spoke loudly, as if the entire field were filled with people he wished to address. And although everyone in the encampment was well dressed for cold, and fashionably so—their jackets looked as if they’d come straight off department store mannequins—only the old man was robed. It was a saffron colored cassock with a large bright yellow satin cross embroidered over an ochre, green and red sunburst that covered his chest and belly. But it too looked as new as everyone else’s clothes, and I figured it had recently been lifted from the sacristy of a nearby church.

“I sympathize with your quest, but I very much doubt it will bear fruit. Everyone is seeing the wisdom of fleeing the darkness of the north and entering unto the land of light, where they will find eternal truth and everlasting salvation.” He lifted his hands to the hypnotizing sunset, mercifully blotted by streaks of orange and purple clouds. “Behold the unmistakable sign for the faithful to follow.” Before we knew it we were surrounded by more than two dozen of his flock emerging from the tent. “Please join us in giving thanks for our blessings and taking of nourishment.” He walked off toward the sunset, mounted a wooden crate and drew the attention of the crowd as he raised his arms and silhouetted himself against the light of dusk. “Let us pray for the guidance of God and His only son, our Lord Jesus Christ, whose return is at hand, to lead us from shadow and sin into cleansing light.”

“Amen,” the people chanted in unison.

He slipped a small black volume from underneath his vestments, and everyone did likewise from the pockets of their new jackets and coats. “Today we take enlightenment from Revelations, Chapter Six: ‘And there was a great earthquake, and the Sun became black, as sackcloth of hair; and the whole Moon became as blood. And the stars of heaven fell upon the Earth, as the fig tree sheds its unripe figs when it is shaken by a great wind. And heaven passed away as a scroll that is rolled up; and every mountain and the islands were moved out of their places. And the kings of the Earth, and the princes, and the tribunes, and the rich, and the strong, and everyone, bound and free, hid themselves in the caves and in the rocks of the mountains. And they said to the mountains, and to the rocks, “Fall upon us, and hide us from the face of Him who sits upon the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb; for the great day of their wrath has come, and who is able to stand?”’”

He closed the book, cradling it in his hands as though it were a hatchling. “Does the Word of God not transcend all time? I ask you, if God can see the panorama of history as easily as you or I can read a calendar, does He not also see into the very depths of our souls? What does He find there? Darkness! Black thought and black intention, as black as the darkness to which great and small, young and old, man and woman alike, fled to hide their eyes from God’s wrath, just as God foresaw that they would.” He explored this tangent for several minutes, leading up to his justification that the assembled were God’s chosen, while the sunset behind him shone like stained glass. Suddenly he raised his arms again and shouted into the faces of his rapturous flock. “Do you believe you are God’s last children?”

“We believe,” the gathering chanted atonally.

I did not make a sound, not necessarily because I did not believe but because the light had triggered the voices in my head, and I would have found it impossible at the moment to open my mouth without spouting gibberish. If I did, the preacher, obviously not a Catholic, would most likely think I was trying to turn his performance into a Latin High Mass.

“Do you believe our Lord Jesus is about to arrive for the Final Judgment, and that the Millennium is at hand?”

“We believe.”

“Do you believe that the star of guiding light is a sign from God...” At that moment a stray breeze caught the scent of the simmering pot and distracted me from the competing brands of gibberish and drivel produced by my head and the preacher. Unnoticed, I sidestepped toward the fire, as careful to avoid looking in the flames as at the Sun. My stomach groaned and creaked when I saw the stew bubbling lazily inside the kettle, carrots and potatoes and onions and peas swimming in a sea of brown gravy, amid chunks—no, islands!—of meat, great archipelagoes of flesh far too big to have come out of any can. The stem of the ladle disappeared into the steamy depths, and I wanted to slide down it and splash around for awhile. I reached for the handle, making sure no one was watching, but at that moment the crowd gasped collectively, and I nearly dropped the thing in the dirt. They were not shocked to discover me giving in to temptation, however; the preacher had somehow produced a hooded gray pigeon that perched on his wrist. It was the first bird I’d seen since September.

“Rejoice!” he cried, “and be glad, for all God’s creatures sense the coming Rapture.” The pigeon fluttered its wings as if in agreement. “Go with the angels, and show us where God’s kingdom awaits!” He snatched the hood from the bird’s head. Startled by the light, it rose almost vertically, flapping itself into tight spirals, before wheeling and shooting off almost, but not quite, in the direction of the sunset. Following instinct as much as any divine compass, it headed south.

I thought the service at an end, as everyone immediately formed an orderly line that led to the gurgling kettle, but there was still one more ritual to attend to. Nearby was a plastic bucket partially filled with water, probably melted snow. The preacher blessed it, asking God for the power to cleanse both body and soul, and then each of the congregation proceeded to roll up his sleeves, scrub hands and arms down, and finally bending over and sticking his head in up to the ears. Though the temperature was no more than a few degrees above freezing, nobody seemed the least bit discomfited. All smiles, they looked up and gave thanks, and in the dying light I could see the wisps of steam rising from their damp brows. I was reminded of washing myself with the water from Gregg’s death-tainted pool—the refreshing, renewing feeling it brought, and Karen’s assertion that water was somehow a defense against the Nova Phenomenon. Then again, after a bout with pneumonia, I was hardly tempted to stand around on a winter evening with a dripping scalp, and then there was the commotion my dye job gone to seed might cause. I began to wonder if baptism was a prerequisite to dining when Gregg tapped me on the shoulder.

“Pete, we gotta split.”

My cheeks ached as my saliva glands mutely protested. “Why?” I stammered. “We’re about to eat!”

“I don’t think it’s a good idea to hang around here. These people are as crazy as LaMaze’s bunch. I’ll get Chris and meet you at the truck.”

To console myself I thought of reasons why I might not want to eat: there was no telling where the meat had come from, for one thing. But the most compelling was that I had no wish to contract pneumonia again. Towels were being handed out as I got back into the truck, and I scrunched down in the rear seat to erase the sight of people being served. Karen’s papers—almost left behind at the hotel in Dallas—crackled beneath my coat, and I immediately began to wonder what Karen would have thought of this. As if the answer might be contained within, I slipped the papers out and began to read them for the first time.

Good morning starshine the Earth says goodbye, was the opening line on page one, and again I wondered about her mental state. It was, I would later discover, a twist on an ancient lyric. Underneath was a rough sketch of the sunrise over El Vado, the light obliterating the horizon and everything else in its path to the observer. Below that was this poem:

raise hell or lower

heaven you

can subtract your

darkness from the dawn

no shadow

cast on

earth is perfect anyway

I flipped through the pages. What had been a seemingly jumbled two dozen or so turned out to be more than sixty. The sketches, poems, and hastily written random thoughts eventually gave way to more coherent discourse, but upon becoming absorbed with a couple of paragraphs I was able to read by the failing light, I discovered the papers were out of order. Karen was postulating that the Moon alone was responsible for humankind’s ascendancy to intellectual prowess. “The Sun was always blinding, an unknowable quantity, while the stars and planets were too dim and stable to distract for long those whose heads were almost always bent downward, searching for survival in the dust. But the Moon, shape-changer, disappearing act, seemingly no more distant than the clouds on the mountaintops, drew a rise which forever separated us from other beasts: wonder.”

I sat up to reach for the dome light so I could begin sorting the pages, but at that moment the passenger door opened and it came on anyway, shocking me like an electrical short. Christine landed in the front seat as if she had been thrown, and the door slammed shut, plunging the interior into darkness. The truck rocked as Gregg leaped and slid across the hood, and before he could open his door I saw the crowd gathering around the vehicle and dimly understood our peril. They were fixated on Christine, pressing up against the right-hand side, craning their necks for a better look. She returned their stares with awe, and a growing smile at the thought of being the center of attention. She pressed her hand to the glass and they responded in kind. She giggled. Gregg climbed in, fumbled for the keys, started the engine, thrust the gearshift into drive. Alarm registered on the faces above the plastic green bug guard at the front of the hood as the truck began inching forward, but those clinging to the sides kept pace. Christine activated the control that rolled the window down, and through the inch-wide gap dozens of fingers wriggled like the tentacles of a mad sea creature. A few voices pleaded in unison for her not to leave, but above them rose a chant that revived every terror, for it uncannily echoed the nonsense rants of the magistrate.

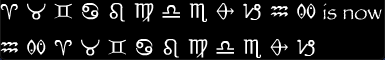

“RAVANESTHUS IMPOLEGO NARI LUMNEXO! VINTO SERIADA KLATOO! HANMY UNTHUPI YESTLETHIS!”

I thought I heard another engine revving, while to the fore the crowd gave way to the Reverend and his two seeming bodyguards. He thrust his palm toward us, dramatically standing his ground three meters ahead while his boys were in the act of drawing their pistols, so Gregg blasted them with the headlights and goosed the accelerator. The Reverend’s cassock blurred like scrambled eggs as he jumped, and an ominous thud sounded from the right fender.

Next