Chicago

Near the city limits, where the freeway bridged the canals, was the impassable wreckage of hundreds of vehicles. After Gregg and I relieved ourselves over the edge, we exited and took the same course along Ogden Avenue. By now the air carried an occasional smoker’s puff of fog, which grew denser as we neared downtown, obscuring the mountainous skyline and the moonlight. When we reached the Eisenhower Expressway Gregg had turned off the headlights because the reflected glare made it impossible for him to see. Miraculously we were able to cross the Chicago River on Jackson Boulevard, and Gregg credited me for the good fortune. Then, without warning, heavy droplets began to spatter the windshield.

“It’s raining,” Christine said in wonder.

“No,” Gregg countered. “It’s the dew dripping from the skyscrapers.”

It was nearly four a.m., and the alcohol had lost some of its kick. Gregg wanted to continue on to the lake, but east of Michigan Avenue the streets became bumper to bumper parking lots, and we finally parked it along with everyone else and walked to Lake Shore Drive, through the ghostly forest of Grant Park. Gregg hefted his shotgun, and I sported Ben’s 9mm pistol, the same one I had used to shoot out the Lone Ranger’s lights, but our reflexes were relaxed. Not a sound permeated the cool sodden air. The westering Moon was a helicopter search light, slowly giving up its hunt and disappearing behind the buildings. Upon reaching Lake Shore we began to run across random scenes of carnage. Many were between and beneath the cars, trucks and buses packed tightly as bricks. We came across a skeleton in a policeman’s uniform, slumped over on a hood, legs crushed in the vise of two bumpers, jaws still parted in a final scream of agony. Even after crossing the wide boulevard there were more cars to contend with—the lakefront park had been converted into a parking lot that sloped down a hill to the invisible harbor. We continued northward, led by a magical multi-colored spray paint line. Nobody spoke, not even to wonder out loud how a city of millions could simply vanish.

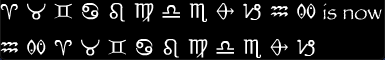

When the twilight began to overtake the sky, filling the air with a cottony luminescence, we stood on the bridge overlooking the mouth of the Chicago, the first river to defy gravity and flow backwards. Here the spray paint line jumped over the railing and my heart skipped a beat as I again thought of Ruth. A westerly breeze stirred, sending the mists back out over the lake, and as the light increased so did the visibility. From our vantage we saw the extent of the eternally frozen traffic jam trailing down from the bridge, from wall to wall along the Navy Pier, back into town on Wacker, even crowded amongst the boxcars at the rail terminal below us. It did not end at land’s end. As the bleary Sun emerged from the lake, diluted to a specter of its former self, looking about the way we felt after all that champagne, the mystery of Chicago’s fate was revealed. Dotting the beach and the waters immediately off shore were the half-submerged wrecks of every vehicle imaginable—cars, trucks, jeeps, buses, semis, even what looked like a car off the El and a motorcycle with a sidecar. The beachhead at Chicago was forevermore impervious to invasion, surrounded by this atoll of iron, but in reality the invaders constructed these defenses and, like the river, reversed their impetus, attempting to overwhelm the lake by sheer numbers, thinking perhaps the Sun might part the waters for them. Gregg and Christine gazed mutely, trying to not even breathe very loudly, and I knew what they were thinking. In spite of the miles we had come and the hell we had been through, we were back where we started. It was no great leap from Karen’s bathtub or Gregg’s pool to this—what Gregg offhandedly called the Sunrise Sea a few days afterward—except that the temptation here was far more grandiose. When I clambered up the railing by the spray paint line they thought I’d given in to it, and Gregg rushed over to save me, but I simply strolled like a tightrope walker out of his reach. He could only stare up at me, shading his eyes, as I shouted the pig Babylonian echoing inside my skull whenever the Sun was up. Immediately my two companions began looking nervously in every direction, as if for the famous Chicago police to arrive and arrest me for disturbing the peace. The layered reverberations through the labyrinths of the city returned with the effect of many voices joining in, as in the singing of a round.

“Quit fucking around!” Gregg growled.

Next