Prologue

It was inevitable that the first time I tuned in Radio Free Luna I would remember Karen, not only because of the symphony they broadcast but also the brewing thunderstorm that marred my reception with crackling static. Upon locking in on the signal on my seven-band receiver, smack in the middle of the AM dial, I yelped for joy and immediately dashed outside to where Sunshine and our two daughters tended the flowerbeds by the evening light, in anticipation of the rain’s arrival. It was latest summer, the halcyon days just before we set to reaping the bounty of our quarter-acre plot, the old apple and pear orchards farther down the mountainside and the piñons higher up for their sweet nuts, to lade our shelves for winter. They had seen me perform the ritual of hauling out the radio once a week or so and listening for anything unusual long enough without success to have lost interest, so the news of my discovery did not enthuse them as much as I hoped. I had to convince them to drop what they were doing and herded them inside, where they sat on the floor before the radio while I hopped on the bicycle generator and began pedaling, scared to death the signal had disappeared in my momentary absence. But the receiver powered up to the sound of an ancient orchestra in crescendo— strings raging, brass blaring, cymbals crashing, drums pounding—all modulated by the fading of ionospheric propagation and shot through with the approaching lightning. The girls, who had already been exposed to recorded music from the collection of tapes we played for them on special occasions, did not fully comprehend their parents’ exultation until the announcer broke in at the piece’s conclusion.

“You have been enjoying the Fifth Symphony by Ludwig von Beethoven.”

He gave his name as Bill Ransom in a pleasant, leisurely baritone, placing special emphasis on soft consonants to be better understood at great distances and above the intrusion of meteorological disturbances. The girls acted as though they had seen a ghost. Capella’s eyes widened and her mouth hung open in disbelief, while Desde Una, the younger by two years, leaped over to the radio and peered through the speaker grille to see who might be hiding behind it. Sunshine and I exchanged glances and little smiles, both amused and a bit apprehensive at the normal reactions of children hearing a stranger’s voice, and a disembodied one at that, for the first time ever.

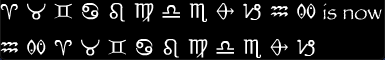

While they displayed their astonishment amongst themselves, Mr. Ransom promised more Evening Classics to come and yielded to another announcer, less mellifluous and more businesslike. Calling himself Professor Science, he raised the subject of the Sun, reminding survivors everywhere that dementia solaris was still a force to be reckoned with, that it was still dangerous to expose oneself to daylight for prolonged periods, and that the upcoming full Moon was the optimum time for harvesting in the northern hemisphere and planting in the more temperate regions of the southern. He thanked us for our attention, and was followed by a third voice, seemingly of a boy just entering his teens, who proclaimed the station’s extraterrestrial identification.

“Bringing all the Earth together under the voice of reason, culture, and hope for tomorrow, this is Radio Free Luna.”

Mr. Ransom returned and introduced Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Eine Kleine Nachtmusic”, but by then the storm blew in over the ridge, heralding its arrival with bursts of thunder and heavy rain, and the melody was constantly peppered with electrical firecrackers. I rode the bicycle generator to a stop, and the audio faded out. “Make it play again!” Capella pleaded. I switched the power over to the windmill and turned on the lamps on either side of our brocaded sofa, for the clouds had dispensed with the evening twilight. I squinted a little against the tungsten illumination, but Sunshine and certainly the girls were not bothered in the least. Desde Una gleefully jumped up and shouted, “It’s storytime! It’s storytime!” and ran to the bookshelf for the stacks of Dr. Seuss, Grimm’s, and antique comic books, while Capella sat by the silent radio and conveyed her disgust with her sister’s short attention span and childish enthusiasm with a sneer. Her mother and I prodded her into joining us on the sofa, explaining that we would be able to hear things much better after it quit raining. Choosing a volume from the table where Desde Una had ceremoniously deposited them, Capella prepared to display the talent for reading she had acquired over the previous year, but I disappointed her again when I took the book from her. “No, honey, that’s okay,” I told her. “This time your Mom and I want to tell you a real story. It’s not in any book, at least not yet, but now is a pretty good time to begin it.”

Sunshine gave me a look of dull surprise and pursed her lips, but said nothing. So I proceeded to indicate the storm’s fury outside our window, reminded them how scared they were of the lightning and thunder when they were smaller. “I like it when it rains,” Capella piped in, and memories of Karen washed over me once more. Ignoring her impertinence, I told of a time, not so long ago, when people became just as scared of the Sun. Pausing to let them absorb the concept, I realized I was stuck for a good place to take up the narrative. Capella took the opportunity to ask if it got really hot and started a fire, like the lightning sometimes did when the forest was dry. I responded that it wasn’t quite that way, that it was more like putting your eye so close to the light bulb that it hurt. Desde Una had actually done it once, as she had with the radio moments before, hoping to catch a glimpse of its inner workings. In asking the question, though, she gave me an idea, and I persuaded Sunshine to help me recount how the cloudburst eight years earlier sent us scurrying for cover under the bed and inspired our friend Gregg to take to the air with his own station. The tale of our adventures with radio waves and other mysteries grew in the telling, although we purposely omitted many details, including the evil major. The girls were enchanted and thrilled as they heard how we chased across the continent, mostly searching for other people to talk to, both on the radio and in person. They wanted to know why old Ben Cody preferred to stay behind in the drowning city. They wondered why we never met Karl, King of Liechtenstein. Most of all, they wished to learn if we would someday venture beyond the mountains again, to find more people to talk to.

“Where are they now?” the ever-curious Capella inquired.

By this time the thunderstorm had done its worst, so I steered the girls’ attention back to the radio. Lowering the seat on the bicycle generator, I harnessed Capella’s nervous energy and everyone cheered Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture” in all its martial glory. Sunshine smiled from her seat on the sofa, after checking on the wind-up clock on the mantelpiece. She knew she might have a fight on her hands once bedtime arrived. Bill Ransom sounded as if he were broadcasting from the next room as he bid farewell, inviting us to tune in again in nineteen hours for more Evening Classics.

He closed with what became his theme song, Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra”, and the youthful announcer in charge of station identification took over. He gave the date as September nineteenth, confirming what I had to guess from a sunset at the base of the Washington Memorial on exactly the same date seven years previous. The correct time, he said, was three minutes after the hour. “How can that be?” Sunshine blurted in amazement. We had been carefully calibrating our clock by ancient newspaper listings of sunrise and sunset times, and yet we were seventeen minutes behind their estimate, so she was naturally a bit put off. Unaware of the furor, he previewed the lineup of programs ahead, and Sunshine took advantage of the break in programming to tell the girls to put on their pajamas, eliciting moans of despair. She only had to stand up and glare at them before they were off and running to their room. From the sofa she padded over to the window facing east, felt for the catch and opened it. A cool breeze poured through, billowing the curtain and carrying the first hint of autumn, not only because of its temperature but also a certain post-rain aroma. She leaned on the window sill and let the breeze caress her face and toss her hair. Then she spoke, as much to the wild world beyond the glass as to me, and betrayed an increasingly good humor that would set the mood for the evening.

“It’s going to be a great night for a fire,” she said.

When the girls returned in their night clothes I was setting a match to the kindling. They welcomed the sight, correctly assuming the first fire of the season meant the chance to stay up well past their bedtime. They were wearing loose robes made of cotton, blue for Capella and white for Desde Una, and carried the straw dolls they helped their mother put together for their Christmas gifts the previous winter. The dolls had corn silk for hair, eyes of Indian blue corn kernels, and clothing cut from old scraps. They were not so much playthings as sleeping companions, and usually only adorned the girls’ pillows once their beds were made in the morning. Sunshine was about to slip away and change for bed herself, but at that moment the boyish announcer was replaced by the shrill, majestic blasts of a pipe organ, droning some ancient hymn. Half a minute of this caused the girls to stare in complete awe and Sunshine to stop at the door to our room, and then the music rolled under a gentle tenor voice who introduced himself as the Reverend Christopher Swan.

“Hello, my friends, and welcome to tonight’s Bible study.”

Sunshine could not contain her excitement. Raising a joyous shout, she hurried back from the bedroom door and stubbed her bare big toe squarely on the leg of a chair, but even the obvious pain did not deter her from praising the entire Trinity for this miracle.

Hobbling over to the fireplace with the girls’ aid, she sat and gathered them to her bosom, the better to make them obediently listen. The lights were beginning to dim a bit, the windmill now slowing in the calmer weather and the batteries that complemented it taking up the slack. I entertained the notion of easing my pace on the bicycle generator as well to simulate a fading signal, but thought better of it. My wife of these many years knew me well enough to intuit any mischief I might be comtemplating almost in advance. “Please turn it up,” she implored.

The Reverend Swan began at the beginning, with Genesis, crediting the Almighty with creating Heaven and Earth. He brought particular emphasis on God’s pronouncement that there be light, a greater light for the day, a lesser for night, and all the stars besides, and paused to give his thanks for the grand design. Staying on the subject, he skipped ahead to Ecclesiastes. “Truly the light is sweet, and a pleasant thing it is for the eyes to behold the Sun,” he said, and paired this quote with one from the Psalms: “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” This, he claimed, exemplified life before and after what had come to be known as dementia solaris. Saint John prophesied a lot on the matter, having written that darkness does not comprehend light, and that humanity loved darkness because its deeds were evil.

“Could we then say,” the Reverend wondered, “that humanity, despite its knowledge of light waves and prisms and telescopes, humanity still held little comprehension of true light?” At the mention of optical devices I stole a glance at Sunshine. She was sitting on the hearth, her back to the fire, the girls on either side of her, seeming to stare at an undefined point in the air. Her arms were around their shoulders, her hands busily stroking Desde Una’s blonde hair and Capella’s much darker brown, but she appeared to be holding them still more than comforting them. I was disappointed that she apparently had no recollection of our final encounter with the major, when I conquered the continent in a day and for a day, and as the Reverend’s patter went on, I began to perceive the little radio as the first unwelcome visitor in our serene home. The girls seemed to share my attitude, if only out of increasing boredom, as they fidgeted and pulled absently at their dolls’ hair and clothing, understanding no more of the Reverend as humanity did of the light.

The sermon mercifully ended after only fifteen minutes, with words of hope and encouragement. Malachi promised that, for those who fear God’s name, the Son of righteousness shall arise with healing in his wings. This was a verse familiar to Sunshine, and she repeated it almost simultaneously. The proverb which spoke of the Lord as the source of light and safety did not escape her notice either. In parting, the Reverend Swan asked us to remember that all the stars in heaven were created to bring light to our lives while we dwell in this world.

“Even Arcturus the Great, which I am told outshines our Sun by a magnitude of twenty, and which you may be able to see now, as I speak, out your western window, following the Sun down.” He then bid us farewell, beseeched God’s blessing for us, and invited all to listen again tomorrow when he would tell us how Joshua made the Sun stand still to confound his enemies.

“You see?” Sunshine said to the girls, as the dreadful organ blared once more. “Everyone reads the Bible!”

The organ faded, another station identification was given, and Professor Science returned to the air with his own fifteen- minute slot.

“Greetings from the Moon!” he began, far more cheerily than his earlier public service message. “It’s nighttime wherever you are, but the start of another bright beautiful three hundred fifty-four hour long day here on the shores of the Sea of Tranquility. Let me tell you a little about my strange and wonderful new home.” He went on to lecture about the Moon’s dimensions, distance from Earth, and why day and night on the Moon were each more than two weeks long. “The Moon only turns as fast as it orbits,” he explained, “so when someone here says it’s been a long day, they’re not kidding!”

I began to find his levity a bit annoying, partly because his upbeat demeanor came across as patronizing, as if he were speaking to a child, and partly because he really wanted his audience to believe he was happily living on an airless rock four hundred thousand kilometers from Earth. Sunshine, still enraptured by the Reverend’s service, only was alerted to the Professor’s con artistry when Capella, who had already asked what a free luna was, began laughing. Thereafter she sat stoically, still grasping her daughters close, as if she had mistakenly walked in on a pornographic movie but did not quite have the nerve or lack the curiosity to leave. She was undoubtedly upset that the girls would pay more attention to the Professor’s outrageousness than the Reverend’s piety, and issued a strong denial when Capella boldly inquired whether God lived on the Moon, too.

“He’s just making up a story!”

The Professor went on to describe the lunar surface, its mountains and craters, and how everything was covered by a dust he called regolith. He stated that ever since human beings first visited the Moon scientists knew that plants could grow much faster in lunar soil. “I wish I could send you some right now,” he said. “You’d have twice as much food on your table after the next harvest.” He concluded with a brief summary of lunar history, told of the courageous Armstrong’s first steps and the words he spoke: “One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Still, after that note of seriousness he could not resist one final gag. “Speaking of leaping, I almost forgot! Did you know if you can jump a meter high on Earth, you can jump six meters high here on the Moon? Let me demonstrate.” At that his voice seemed to move farther away from the microphone, as if he were on the other side of the room, then quickly bounced back, and repeated the effect several times. “THAT’S BECAUSE THE Moon’s gravity is ONLY ONE-SIXTH that of Earth’s. THAT’S ALL THE time I have FOR TODAY! UNTIL next time, so LONNNNGGG! WHOOOOooooaaaahhhh!” Then his bouncy theme song faded up, and by then the girls had escaped from their mother’s hold and were jumping up and down in imitation of the crazy Professor. Only the threat of a quick bedtime suppressed their enthusiasm.

The next segment, Luna Library, was introduced without the fanfare of a theme song. “Tonight’s feature is Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” said the young announcer, who I assumed was also the engineer for the broadcast. Then a far more distinguished voice repeated the book’s title, and began his reading with the first chapter. His elegant manner and resonant projection had a sedating effect. As they usually did when we read to them, the girls settled down, and Sunshine, regaining her generous frame of mind, escorted them over to the sofa and began braiding their hair with brightly colored yarn. As the narrator read on I realized why the material, ancient as it might be, was selected— the bucolic life we were leading had more in common with the mid-nineteenth century than more recent times.

Still, there were plenty of oddities that might require explanation for the youngsters, if they had been paying more attention, like steamboats and slavery, and even school. Then there was the way people of that day and age talked, for the narrator had a way of affecting his speech whenever describing dialogue, and by the time he had begun the second chapter I understood the voice belonged to a once-famous Hollywood actor, now long dead, and not to anybody associated with the station. It was undeniably a superb choice for what had to be the premier broadcast of Radio Free Luna, though, and after the performances of the Professor and the Reverend, the irony of Tom’s deviousness in the whitewashing incident and his discomfort in church were not lost on me. It also renewed the memory of the spring morning when we finally crossed the Mississippi at Hannibal, and Sunshine and I touched for the very first time in a way that was even remotely affectionate.

The reading ended after five chapters, with the promise of resuming it the following evening. Sunshine was yawning as she finished Desde Una’s hair and began on Capella. They had been listening, but not intently, and as the boy announcer touched on the date’s noteworthy events in ancient history I arose to stir up the fire, deciding against throwing another log on for a few more minutes. If the trend of the last hour continued and one more story or lecture or sermon was about to air, we might as well all go to bed.

There would be plenty for us to do tomorrow in preparation of the imminent harvest, and our captivation with this novelty already was reaching its limit. Or so I thought. In another moment a new voice, or rather one from the very earliest days of radio, judging by the peculiar inflection, greeted us. “Good evening ladies and gentlemen, and all the ships at sea.” A syncopated drumbeat led into a swing number from the Big Band era of popular music, trumpets and trombones and saxophones fronting a swift rhythm charged by an arrangement in a minor key. It was music made for dancing, and even if everyone in the world had forgotten how, there was no denying its rousing appeal. There was certainly nothing like it in our collection. Even little Desde Una, who had been fighting a losing battle with her drooping eyelids, sat up straight, the driving melody reinvigorating her determination to stay up as late as a five- year-old could. Capella began to bounce her doll on her knees, and at the song’s climax threw it up in the air, where it flipped end over end like an acrobat. Sunshine lost her patience and threatened not only to send her to bed but undo the work on her hair as well. She was almost done anyway, and upon being dismissed Capella conveyed her hurt by retrieving her doll from the floor, tramping over to the open window and concealing herself in the drape. Her self-imposed exile did not last long, however, for the breeze ruffling the curtain had taken on a decided chill. She soon made a beeline for the hearth, and as consolation for her reprimand I let her put another piece of wood on the fire.

It looked like we might be up a while yet. The music segued into a slower piece but still with a distinctive beat, and as the song progressed to the bassist’s solo our host for the night’s festivities addressed his audience. “Hello hello hello,” he crooned. He sounded like the kind of guy who, in another life, spent a great deal of time sweet-talking women in bars. His glib, easy-going style was at once in stark contrast to the clip of the stiff old announcer he would end up opening his show with for the next several weeks. “Many heartfelt salutations to our pale blue companion, from all of us at Radio Free Luna. They call me Ken the Kidd— that’s two Ks and two Ds, please— and except for my mandatory space helmet, I’m going to do my program tonight completely naked.”

“For heaven’s sake!” Sunshine exclaimed. Capella giggled at the wisecrack and her mother sharply reminded her to mind her manners, that good girls did not think nudity was any laughing matter. Capella was humbled into apologizing for her misbehavior, and further chastened as Sunshine made good on her earlier threats, saying they were both headed for bed. Both protested and appealed to me to spare them, but I told them they had to do as their mother said. If they had been boys I probably would have acted otherwise. As it was, I let Sunshine assume nearly total control over their discipline and moral instruction, from their twice-weekly Bible readings to wearing bathing suits when they went wading in the creek. At least Ken the Kidd did not say anything for another ten minutes or so, just let the music play, so Sunshine managed to get them squared away and off to their room without further controversy. He opened the mike briefly as she came back out to tell me goodnight. The song playing was a soft, sensual piano number with a samba rhythm, and he dedicated it to lovers everywhere.

“You still do love each other, don’t you?” he wanted to know. If she heard him as she kissed my cheek she pretended not to.

At any rate she knew better than to prod me into coming to bed before I was ready, whether I was listening to some merry prankster on the radio or just sitting out in the yard staring at the stars. When she closed the door to our room I got off the bicycle generator I had been leisurely turning for more than an hour, shut off the lamps and plugged the radio into the batteries. Now that it was almost midnight skywave conditions were ideal, so my reception was crystal clear and nearly unwavering. That was something I learned about from Gregg, and as I stretched out on the sofa I wondered how he would react if he could hear the station. I was certain that Karen would be loving every minute of it, with the exception of Reverend Swan’s sermonette. She would have swooned over the symphonies and concerti, and found plenty of amusement in the Professor’s antics and Ken the Kidd’s tongue-in-cheek humor. She would even love the name the station had been assigned. It was from her, after all, that I had learned about the importance of the Moon, the Sun and all the stars in our lives, and how to spot a grand deception, too.

She would also have been intrigued by Ken the Kidd’s detailed weather outlook, expedited by his unique vantage point. “Looks like an early snow for the northern Rockies, and a damp harvest for the prairies tomorrow. Kind of hard to tell from this far away, but there seems to be a hurricane starting to spin in the mid-Atlantic, too.” He promised to keep folks along the coast up to date, and led into a lively piece with what he called a mad xylophonist at work. I told him he forgot to mention scattered thunderstorms in the Southwest, and wondered silently if he were any less sane than the xylophonist, making up the weather as he went. At that moment I heard a rustle from behind the couch, and Capella emerged wrapped in the coverlet from her bed, to ask if the man in the radio could hear me talking to him.

“Maybe,” I said. I moved over on the couch to let her lie beside me, spreading the coverlet over both of us.

She whispered when she spoke so as not to awaken her mother, wise enough to know Sunshine would disapprove not only of her sneaking out of bed but wanting to hear more of the naked man’s show. Her dark eyes mirrored the fire’s glow as she gazed into it, and when I brushed a few strands of hair from her face and yanked playfully on the yarn she smiled at me. It was an ingenuous grin, made all the more childlike by a missing tooth, that still communicated a sort of conspiratorial satisfaction. Ever since she became cognizant of strictures like bedtimes and clothing, she was also aware of my tendency to play the foil to her mother’s stern character. Without confronting or contradicting Sunshine directly, I rather would maintain my silence or look the other way when Capella committed some harmless peccadillo like helping herself to a spiced apple before supper. Twice during the passing summer she had appeared at my side as I meditated on the midnight sky, once on a sparkling clear full-Moon evening, and again when lightning flared above the peaks to the north. Seeing the fire flicker in her eyes reminded me of how she watched in silent awe as the bolts illuminated her features, while on the moonlit night she was full of questions, whispered as much in reverence as for stealth. She wanted to know why the Moon didn’t feel warm like the Sun, and I told her it was because the Sun was burning and the Moon was cold. “Is it covered with snow?” she asked. Keeping the scope of her inquiry within bounds she could conceptualize, I gave an ambiguous answer. At the time, I reasoned that the idea of ancient humans going there and back was beyond her understanding. She then surprised me by daring to challenge the biblical cosmogony she had been learning at her mother’s knee.

“Mommy said God made me and the stars and everything. Is that right?”

For a fleeting moment I toyed with the notion of denying it all. Remembering how Sunshine got religion in practically the same week she thought of both Gregg and me as conveniently dead still pained me. But destroying the child’s confidence in her mother over a long-gone grievance horrified me more. “Yes,” I told her. “He’s just getting started, too.” She took it as a compliment and smiled.

Ken the Kidd gave his own station identification and began the next hour of his show with a sound effect of a radio dial, back in the time when it was filled end to end, being spun. Eerie music faded up, and he announced menacingly, “Do not adjust your set. We have taken control of it.” Then he was again his suave, debonair self, and asked laughingly if we believed there was a day, not so long ago, when people would actually say that over the air. “Those of you who were listening earlier heard my pal Professor Science describe the exciting real estate acquisition we call home. But he left it up to me to tell you the story of how we got here.” Ken began with the premise that he had been an astronaut, crewing the North American space station. The others— Bill Ransom, Professor Science, and someone he called Corky, which was either the kid engineer’s name or his moniker for the Reverend— were his shipmates. They had the fortune, or perhaps misfortune, of being aboard when dementia solaris swept the planet. The news from Mission Control that something was wrong reached them just as Ken was completing a spacewalk to repair a solar panel. He said they couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about, especially since they were on the dayside of the orbit at the time. The reports that followed were sporadic and often contradictory, but always more ominous than the last, until finally the link with home vanished forever. In the time it took their craft to complete a dozen revolutions of the globe, civilization as they knew it had gone the way of the dinosaur.

The music he spoke over blended into a dirge, ponderous and melancholy. “There were no clues whatsoever as to what really happened, Watson,” he intoned with a British accent, then resumed his normal voice. “One thing we were all sure of, though— if we returned to Earth we would undoubtedly suffer the same fate as the rest of humanity.” However, they could count two bits of good luck in the midst of their predicament. First and foremost, the shuttle that ferried the astronauts and their provisions from Earth was docked alongside. Secondly, they had managed to make contact with the space lab carrying their Russian counterparts several thousand kilometers distant and establish a halting dialogue. Only one of the Russians knew English, and just a little at that, while neither Ken nor his crew could tell da from nyet. Nevertheless, they got enough across to work out the mechanics of a rendezvous that would take thirty-seven hours to close. Once a crude attachment could be fastened, the two vessels would fire their boosters together to achieve escape velocity and set a course for the nearest safe haven in this mythic tempest, the Moon.

Capella lay quietly in my arms as the story unfolded, but her eyes still held the fire within them. I wondered how much she could understand, considering my recent attempt to confuse her as to the Moon’s composition, saying it might be made of snow. “They’re going to the Moon,” I blithely summarized for her.

“Yeah,” she sniffed, as though she were way ahead of the game.

The mood music changed over to an ethereal wash of synthesizers while Ken told of the anxiety that prevailed as the abyss between the two worlds loomed before them. They all knew it was an enormous gamble, but a calculated one nonetheless. Both missions had several months’ worth of freeze-dried and concentrated nourishment between them, but also lab animals and a variety of seeds for zero-gravity experiments. Advanced equipment could recycle air and waste products “till the cows come home“. They had acres of solar panels for power. “Just like our bike and windmill,” I said to Capella, who shooshed me. There was just one problem. A lot of fuel had been burned to escape Earth’s gravity, and only enough remained to inject them into lunar orbit. They would not have anything left to execute a safe landing.

Dark, tension-building music underscored Ken’s description of their dilemma, of how the Russians accused his crew of sending them all to their deaths. They even threatened to detach their compartment and use the fuel that remained to them to return home. Considerable diplomatic effort, made no easier by the language barrier, finally persuaded the Russinas to stay on the team. “We agreed to let them wear our jeans,” was Ken’s cryptic comment on the conflict’s resolution. Actually, Professor Science had come up with a plan to supplement the dwindling fuel supply. Among the North American crew’s provisions were several cases of soda pop.

At the point in the landing procedure when the fuel ran out, they would simply refill their tanks with the beverage and spray pressurized foam from the exhaust ports to slow their descent. In the middle of elaborating on the critical maneuver into lunar orbit and the harrowing free fall to the surface, Ken even cut away to an ancient advertisement for a carbonated soft drink to heighten the suspense. Like the opening clip, it also sounded as if culled from the earliest days of broadcasting, with its orchestral arrangement and multiple doo-wop harmonies. Capella, who had neither heard a commercial nor drunk a soda in her life, was mystified by the break in the action. “What a short song!” she laughed. It reminded me of something Ben once told me, that the noise of high commerce was anything from hypnotic to nearly intolerable to anyone who wasn’t born into it.

The story had a happy ending, of course. After breaking down the delicate solar panels and stowing them in the shuttle’s cargo bay, everyone clambered aboard the winged vehicle for the final approach. The two space stations were jettisoned and allowed to crash near the chosen landing site, where they could be salvaged.

Although the Moon had no atmosphere for the shuttle to glide in on, they would be able to use the craft’s landing gear to roll to a stop on one of the vast, flat volcanic plains, using the last of the soda pop to attain the proper angle on their target. Even the mutinous Russians, as it turned out, contributed to the braking maneuvers. “Those guys had a ton of beets and cabbage,” he said, leaving it to the audience’s imagination to figure it out. While still on the subject of food, he quickly added, he wished to dispel the Earthling notion that his home was made out of green cheese. “It’s closer to Swiss, actually“, meaning the Moon had thousands of cavernous hollows beneath its surface, many containing gases left by long-extinct volcanic activity. Although this air was at best unbreathable, it held the possibility of living beyond the confines of the ship without cumbersome environment suits to protect them from the perfect vacuum of space. They would simply have to carry an oxygen supply wherever they wandered in the underground maze. With the background music matching Ken’s springtime optimism, he ended his tale by detailing the ongoing transformation of their forbidding habitat.

The plants and animals they brought gave them enough to eat. The waste recyclers were slowly but surely converting the sublunary atmosphere into one rich with oxygen, freeing them from life- support burdens. They would still make occasional trips to the surface for items from their old vessels, and it was only a few months ago that they finished reconstructing one of their telescopes. Sure enough, the dim sparks of our home fires were popping up all over Earth’s dark side, prompting the completion of a powerful transmitter originally designed to beam a distress signal. Since a rescue mission did not seem likely, considering the recent worldwide decline in technological prowess, they decided to let us know they were fine for now, and to entertain us instead. “Speaking for myself, I’m not sure I could stand returning to normal gravity,” Ken quipped, adding that he’d grown another twenty centimeters during his extended vacation. “But if y’all ever do make it up here, let me give you one piece of advice.

“Bring plenty of women!”

The dull orange embers foretold the approaching dawn. Ken the Kidd had resumed normal programming, rolling the tunes with only the sparsest commentary. The featured attraction at an end, Capella lay asleep at my side. I got up, closed the window, disconnected the radio, and scattered the ashes. Grasping a candle, I carried Capella to her room and tucked her in alongisde Desde Una. Her eyes opened while I contemplated her by candlelight, but she quickly turned over and did not even respond when I wished her sweet dreams. On the coldest winter nights Sunshine and I would bring the children in to sleep with us, and there I was, in a warm bed with three females while the rest of the world, or what was left of it, shivered in implacable solitude. Though I did not pray in earnest to my wife’s deity, I was by the hour increasingly grateful for my life and family, and directed my thanks instead to Karen. During the brief time I knew her she continually displayed a mystic familiarity with the workings of the Universe and, I presumed, with the Creator as well, so it followed that she would be happy to pass the sentiments on. Watching Capella slumber reminded me again how much she was like my first lover, not in resemblance so much as her budding, ever-reaching intellect, and I assured myself that she would come to understand why, unless our circumstances changed a great deal, I would seduce her just as Karen seduced me, at the tender age of sixteen.

Sunshine awoke as I crawled in beside her. I thought of going back to the sofa to sleep, in order not to disturb her, but decided to test the resilience of her good humor. She rolled over and pinned my chest with her elbows.

“You let Capella be a bad girl tonight,” she growled, her face in mine. But she was not displeased with me, since my punishment was only having to endure a few minutes of tickling. I put up just enough struggle to keep from laughing boisterously and waking the children, until her busy fingers found subtler but no less responsive pursuits. Knowing how she enjoyed almost any form of sensory stimulation, I threw the window wide to let the cool sweet night air in. Knowing how I craved visual arousal, she permitted the lighting of several candles. Goosebumps overwhelmed our flesh as we unsuccessfully tried to lick them away, hillocks and hummocks of skin that cast polka-dot shadows in the wavering illumination. Even her breasts hardened in the frosty air, diminishing the effects of nursing and gravity. As the temperature dropped our breath became visible, and we played for a moment by blowing warm steam on cold body. Finally, like the first time, she climbed topside to impale herself, and I fanned her passion with her most impossible fantasies. “Cheeseburgers!” I blurted. “Chili dogs! Strawberry milkshakes!”

She didn’t miss a beat. “Orange juice. Shrimp cocktail. Lasagna!” she moaned.

“Peanut butter!”

“Chocolate-covered cherries! Oh heavens!” The imminent harvest, bountiful as never before, still took a back seat to these trifles, and now it would be set back a day. Not until the Sun broke through our east-facing window to anoint our trembling bodies with its blessing did we rest.

The following evening, almost twenty-four hours after my discovery of Radio Free Luna, the girls and I stood among the tomato vines and tall corn of our quarter-acre plot. Sunshine stayed inside preparing supper, the radio set up in the kitchen to catch the tentative signals of symphonies that were beginning to fall from the darkening sky. There was a little picking to do, some tomatoes, a few ears, but mostly weeds. The girls weren’t much help. Capella had spent a good part of the day feeding and looking after Desde Una by herself while their mother and I slept in, and regaled her little sister with her own version of the science fiction story Ken the Kidd told in the middle of the night. As a result, they were alternately stopping to stare in awe at the half-Moon, slung low in the aquamarine heavens, barely clearing the pinetops, and barraging me with questions.

“That’s where all the people live now, Dusty,” Capella informed her sibling, calling her by the nickname she made up herself. I asked for the dozenth time for their assistance, and they obligingly ran up to where I was toiling. They tossed a small bundle of weeds I had pulled into a basket, and Capella took her pay for the task by bothering me with another question.

“Is that water on the Moon?” She indicated the dark blemishes on its face. In ancient times children were given the impression that there was a Man in the Moon, that the dark spots formed his visage when the Moon was a crescent. To revise the tale for the sake of the first generation of Aquarians seemed only natural.

“Yes, the snow melts in the daytime.”

Now it was Desde Una’s turn. “Daddy, can we go there, too?”

And I had to laugh, thinking of us setting sail on the solar wind across the deep and perilous ocean of the sky, beaching our humble wooden vessel on the regolith strand, only to find I had delivered the women in my life into the clutches of a reluctantly celibate disc jockey named Ken the Kidd.

Back to homeNext